Wild Data

Rewilding Principles

Our Ethos

Rewilding is a conservation approach that seeks to restore self-sustaining ecosystems by reinstating natural processes, species interactions, and dynamic habitats, rather than focusing solely on individual species protection. Central to rewilding is the reintroduction or support of keystone species, such as large herbivores and apex predators, which shape landscapes through grazing, predation, and other ecological interactions. By prioritizing ecological function over human management, rewilding aims to increase biodiversity, enhance ecosystem resilience, and allow landscapes to evolve with minimal intervention. This philosophy draws on both historical ecology, by understanding past ecosystems and species distributions as well as contemporary conservation theory, emphasising the importance of process-led restoration over static preservation.

Natural Regeneration

Natural regeneration is the process by which ecosystems recover through the spontaneous growth of plants from seed, root, or resprouting, without intensive planting or landscaping. In rewilding, it allows vegetation to return in forms best suited to local soils, climate, and wildlife, creating structurally diverse habitats that support a wide range of species while reducing the need for human intervention.

Grazing Ecology

Grazing ecology examines how herbivores shape ecosystems through the plants they eat, the habitats they create, and the ecological processes they influence. Different grazing animals select plants in distinct ways, altering vegetation structure and species diversity. By creating mosaics of short turf, tall grasses, and scrub, grazing drives habitat heterogeneity that supports a wide range of wildlife. The balance between grazers and browsers is central in influencing Knepp’s dynamic landscapes.

Disturbance

Disturbance refers to natural events or processes — such as grazing, flooding, fire, or storms — that disrupt ecosystems and create opportunities for new growth and habitat change. In rewilding, allowing or mimicking natural disturbance is essential for maintaining a shifting mosaic of habitats, supporting species that depend on dynamic conditions rather than static, uniform landscapes.

Ecosystem Engineers

Ecosystem engineers are species that significantly modify their environment, creating or altering habitats in ways that benefit many other organisms. In rewilding, species such as beavers, wild boar, or large herbivores act as ecosystem engineers by shaping wetlands, turning soils, or maintaining open ground, thereby boosting biodiversity and restoring dynamic natural processes.

Reintroductions

Reintroductions involve the deliberate release of species into areas where they have been lost, with the aim of restoring their ecological roles and interactions. In rewilding, reintroductions can revive missing functions, such as predators regulating herbivores, beavers engineering wetlands, or grazers shaping vegetation. This helps to rebuild functioning ecosystems and trigger self-sustaining natural processes.

Trophic Cascades

A trophic cascade occurs when changes at the top of a food web trigger effects that cascade down through lower levels, influencing herbivore populations, vegetation structure, and ultimately whole ecosystems. In rewilding, restoring missing predators or large herbivores can initiate these cascades, driving habitat diversity and ecological resilience through natural processes rather than direct management.

Habitat Connectivity

Habitat connectivity refers to the way landscapes allow species to move, disperse, and interact across space. Corridors such as hedgerows, rivers, or uncultivated strips link fragmented habitats, enabling wildlife to find food, mates, and shelter, and to adapt to pressures like climate change. In rewilding, enhancing connectivity is vital to restore natural population dynamics, gene flow, and ecological processes across larger, joined-up landscapes.

The Wild Herd

At Knepp, a dynamic assemblage of grazing and browsing animals acts as ecological proxies for extinct species, shaping the landscape through grazing, browsing, rooting, and trampling. By performing these natural functions they maintain a mosaic of habitats, boost biodiversity, and help restore ecosystems.

Learn more about Knepp’s ‘Big Five’ and their associated ‘Proxy Species’ below.

Old English Longhorns

Fallow Deer

Red Deer

Tamworth Pigs

Exmoor Ponies

Proxy Species

Proxy species refer to the wild animals that shaped British landscapes before their extinction. Old English Longhorn cattle act as a substitute for aurochs, grazing in ways that open grasslands and maintain habitat diversity. Exmoor ponies stand in for the tarpan, their selective grazing and trampling helping to create structural variation in vegetation. Tamworth Pigs replicate the rooting behaviour of wild boar, disturbing soil to encourage plant regeneration and invertebrate diversity. Meanwhile, Red and Fallow deer predominantly perform natural browsing, controlling scrub and promoting a mosaic of open habitats.

NOT OUR IMAGES – CHANGE THESE BEFORE GO LIVE!

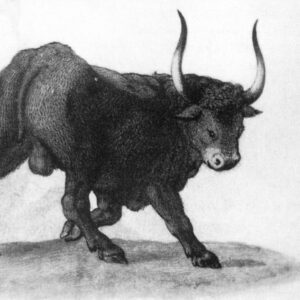

Aurochs

The aurochs (Bos primigenius) was a massive wild ox that once roamed Europe, including Britain, shaping landscapes through grazing until its extinction in the 17th century.

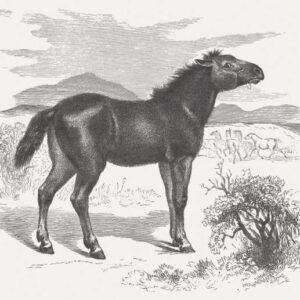

Tarpan

The tarpan (Equus ferus ferus) was a small, hardy wild horse of the Eurasian steppes, last seen in the 19th century, which played a key role in shaping open grassland habitats through grazing.

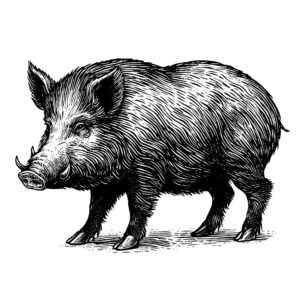

Wild Boar

The wild boar (Sus scrofa) is a robust, adaptable omnivore once native to the UK, extinct by the 17th century and now reintroduced, which shapes woodland and grassland ecosystems through rooting, grazing, and seed dispersal.